The virtual reality of tumors

„Can you tell me why there is still no cure for cancer?“ a fellow party guest asked after I told her what I do for a living. She did not quite seem convinced by my explanation: Cancer is not just a single disease. It’s a moving target, characterized by heterogeneity at all levels imaginable.

Was it a feeble excuse? I don’t think so. Is the tumor blood-borne or solid? In which tissue does it originate? Which genes have gone out of control? Which protein pathways are affected? How does the tumor interact with surrounding tissue? Can immune cells infiltrate it?

And this complexity continues at the cellular level. Cancer stem cells, dormant cells, cells about to become circulating tumor cells and eventually metastases – the list goes on. Inside every cell, epigenetic patterns change within seconds, genes move from one chromosome to the other, increasing malignancy or opening up new survival pathways to evade cancer treatment.

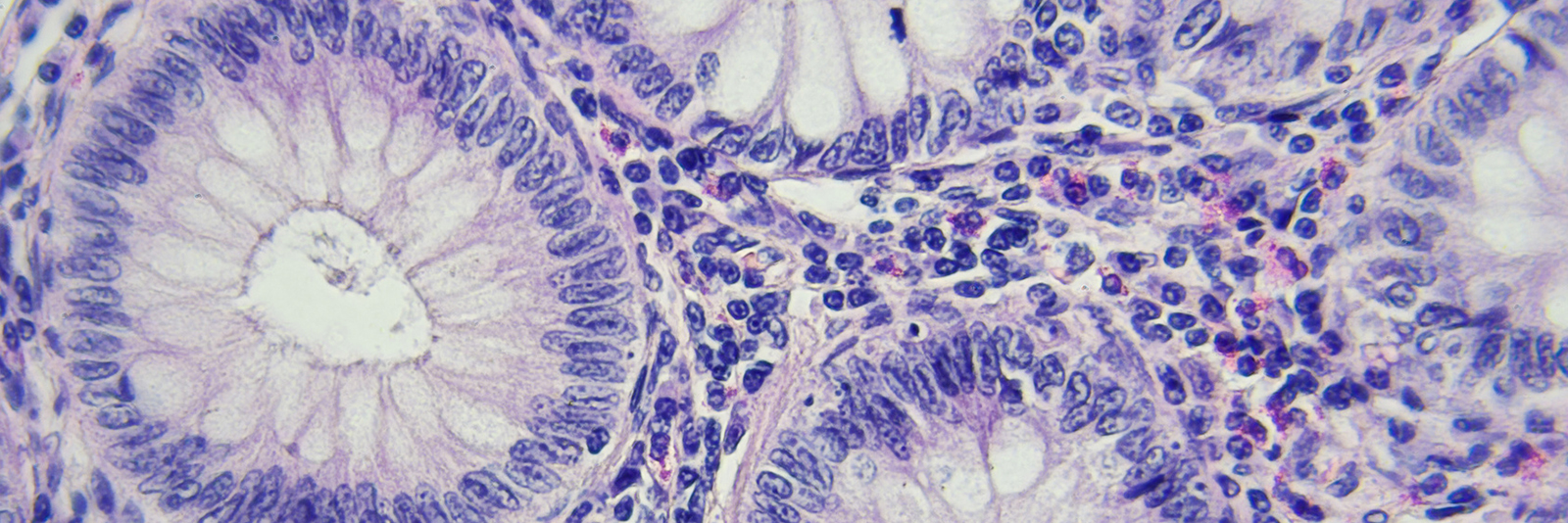

Researchers at the Hannon Laboratory at Cambridge University, UK, wanted nothing less than to visualize this complex picture, so they set off to create a 4-dimensional, interactive tumor map. Starting from a biopsy cut into microtome slices, they applied a novel microscopy technique called serial two-photon tomography to reconstruct whole-organ, multicolor 3D images at single cell resolution.

By combining a multitude of methods – from multiplex immunohistochemistry to in situ DNA and RNA sequencing – they characterized every single cell from as many angles as possible. And to address the fourth dimension – time – a genomic lineage register was set up to keep track of cell parentage over the course of disease progression.

First results were presented on the BBC on December 26, 2018, visualizing a virtual tumor based on breast cancer biopsy material. The BBC journalist – in the form of a scientist avatar – could barely hide his fascination as he explored a virtual tumor magnified to several meters across. He marveled at the arrangement of different cell types and watched as some of them broke away from the main tumor mass, potentially setting off to spread to surrounding tissue.

I like this approach very much for several reasons. First, it is an excellent way to visualize the concept of tumor heterogeneity to a broader audience. Second, it will pave the way to a new scientific understanding of tumors, and hopefully even to the development of new therapy approaches.

What is more, all virtual tumor maps will be available online, enabling the participation of scientists who don’t have access to the expensive infrastructure needed to create such data. All it will take to contribute to new therapies is education, commitment, a laptop and an internet connection. Together, one day, we might even find a cure for cancer.